Manufacturability: definition and scope

Manufacturability describes how feasibly, consistently, and economically a part can be produced using a specific manufacturing process at a given volume. A highly manufacturable design fits the process naturally—short cycle times, standard tooling, achievable tolerances, minimal secondary operations, and predictable yield.

The term is sometimes used interchangeably with design for manufacturability (DFM), but the distinction matters: manufacturability is the property of a design; DFM is the practice of improving it. You assess manufacturability to find problems. You apply DFM to fix them.

- Can the geometry be produced by the intended process without workarounds?

- Will it meet spec reliably at production volume with acceptable scrap/rework?

- Does it avoid avoidable cost drivers like extra setups, secondary ops, or over-tight tolerances?

On this page

- Manufacturability is a spectrum

- How to assess manufacturability

- Manufacturability checklist (10-point)

- Common manufacturability issues by process

- How DFMA Should Costing connects to manufacturability

- Manufacturability improvements with cost impact

- Manufacturability vs DFM vs DFMA

- FAQ

- Sources & further reading

Manufacturability is a spectrum

Most designs are technically "makeable." The question is whether they're makeable well—at the right cost, quality, and throughput. Manufacturability sits on a continuum:

| Level | What it looks like | Typical symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Design fights the process | High scrap, long cycles, multiple setups, secondary ops, supplier pushback |

| Moderate | Producible but not optimized | Acceptable yield but unnecessary cost drivers remain; quotes higher than target |

| High | Design fits the process naturally | Short cycles, standard tooling, achievable tolerances, high yield, multiple sourcing options |

The goal of manufacturability assessment isn't to reach "perfection"—it's to identify the design decisions creating the most cost and risk, and change them while changes are still cheap.

How to assess manufacturability

Manufacturability assessment asks: given the intended process, material, and volume, where does this design create unnecessary cost or risk? The assessment can be informal (design review with manufacturing engineering) or systematic (DFM software with process-specific models).

- Geometry feasibility: Can features be formed/cut/molded without workarounds?

- Tooling requirements: Standard vs. custom tooling? Special fixtures?

- Cycle time drivers: Which features extend cycle time (deep pockets, thin walls, cooling)?

- Setup complexity: How many orientations/setups are required?

- Tolerance achievability: Do specs exceed typical process capability?

- Yield risk: Where is scrap/rework most likely?

- Concept stage: Screen process alternatives and flag showstoppers

- Early CAD: Quantify cost drivers and iterate geometry/specs

- Pre-freeze: Validate final design against process constraints

- Supplier engagement: Use assessment as basis for should-cost discussions

- Production feedback: Close loop on actual vs. predicted issues

Manufacturability checklist (10-point)

Use this quick checklist in early CAD reviews. If you answer "no" to any item, you've found a high-leverage DFM opportunity.

- Process + material + volume are consistent (no "prototype process" assumptions for production)

- Critical features are feasible without special workarounds (EDM, hand finishing, unusual tooling)

- Tool access / part orientation supports efficient setups (no hidden "extra setup" surprises)

- Tolerances align to what the process normally holds (tight only where function demands it)

- Surface finish requirements are limited to functional / customer-visible areas

- No obvious cycle-time drivers are unaddressed (deep pockets, thin walls, cooling, long tool paths)

- Geometry avoids yield killers (warpage risk, thin ribs, sharp corners, stress concentrations)

- Secondary operations are minimized (deburr, ream, tap, coat, inspect, rework)

- Material and specs allow multiple sourcing options (not overly restricting suppliers)

- Key assumptions are documented (volume, material, finish, inspection plan, critical-to-quality dims)

Common manufacturability issues by process

Every manufacturing process has its own constraints and failure modes. These issues often drive the largest cost and schedule impacts:

- Non-uniform wall thickness → sink, voids, warpage, longer cooling

- Insufficient draft → sticking, drag marks, die wear

- Undercuts → side-actions/lifters increase tooling cost and maintenance

- Sharp internal corners → stress, flow hesitation, cracking

- Small internal radii → small tools, slow feeds, more passes

- Deep narrow pockets → deflection, chatter, poor finish

- Over-tight tolerances → extra setups, slower cuts, more inspection

- Poor setup access → more orientations, fixtures, time

- Tight bend radii → cracking, springback inconsistency

- Holes too close to bends → distortion during forming

- Non-standard gauges → availability and lead-time issues

- Over-complex forming → more setups and tolerance stack risk

- Varying wall sections → porosity, inconsistent fill

- Insufficient draft → poor ejection, die damage

- Deep cores / thin ribs → shortened die life

- Tight as-cast tolerances → forces unnecessary secondary machining

A common pattern: specs that seem minor on a drawing (a tight radius, an extra setup, a finish callout) become real cost drivers in production. A manufacturability assessment makes these trade-offs visible before they're locked in.

Want to see what's driving cost on your part?

Grab the checklist for a quick self-assessment, or send a cost-critical part (STEP + volume + material) and we'll build a should-cost that shows where the money is.

How DFMA Should Costing connects to manufacturability

Most manufacturability checklists tell you something might be a problem. DFMA Should Costing tells you what it costs.

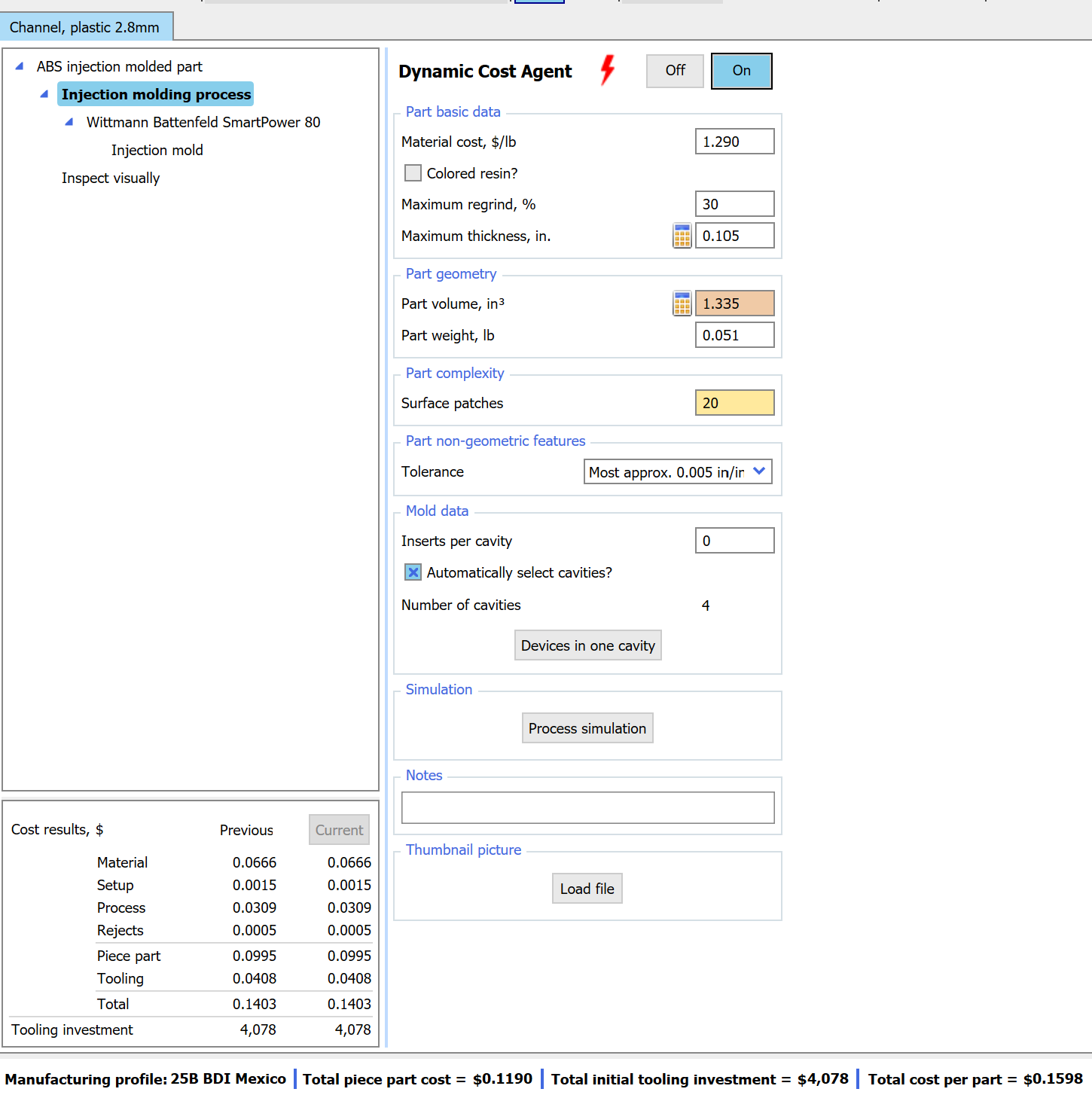

The software doesn't scan geometry and return pass/fail flags. Instead, it models each manufacturing process from first principles—process physics, machine capability, material behavior, tolerances, and finishes—so that when you describe a part's features and specs, you get a transparent, step-by-step cost build-up. Change a tolerance, switch a process, simplify a feature, and see the cost move immediately.

That makes it a powerful manufacturability tool in practice: the features and specs that hurt manufacturability are the same ones that drive cost. DFMA's Dynamic Cost Agent ranks those drivers by impact, so teams know exactly which changes deliver the most savings—and can show suppliers why.

- Builds should-costs from process physics, not rules of thumb or historical quotes

- Covers major processes: machining, injection molding, die casting, sheet metal, forging, and more

- Surfaces the biggest cost drivers automatically via the Dynamic Cost Agent

- Shows cost sensitivity to tolerances, finishes, features, and process alternatives

- Lets you iterate: change a spec, re-run, see the cost impact instantly

- Cost makes trade-offs concrete: "tight tolerance here adds $X per part" is more actionable than "consider loosening"

- Process comparison: evaluate machining vs. molding vs. casting for the same part at the same volume

- Defensible basis for supplier conversations: share the assumptions behind your estimate, not just a target price

- Early visibility: run a should-cost at concept stage before tooling or supplier commitments

Manufacturability improvements with cost impact

Small manufacturability improvements can produce outsized savings. The examples below are illustrative and will vary by material, machine, supplier capability, and volume.

Example 1: Machined bracket — internal radii and tolerances

Assumptions (example): 6061-T6, CNC mill, mid-volume production, same supplier and finish; only geometry/spec changes shown.

| Change | Before | After | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal corner radii | 1 mm (small tool) | 3 mm (larger standard tool) | Cycle time ↓ (typical) |

| Tolerance scope | Tight across full face | Tight only at interface | Inspection ↓, setups ↓ |

| Surface finish | Fine finish everywhere | Fine finish only where needed | Secondary ops ↓ |

Result: cost reduction depends on the baseline, but these changes typically reduce cycle time and inspection effort without impacting function.

Example 2: Injection-molded housing — wall thickness and draft

Assumptions (example): thermoplastic, production tooling, stable resin and color; wall thickness + draft optimized to reduce warpage/cooling risk.

| Change | Before | After | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall thickness | Non-uniform sections | Uniform wall + ribs | Cooling time ↓ (typical) |

| Draft angles | Marginal | Standard | Ejection quality ↑ |

| Undercuts | Multiple side-actions | Reduced via snap redesign | Tooling cost ↓ (possible) |

Result: fewer side-actions and more uniform walls typically reduce tooling complexity and cycle time while improving yield.

Example 3: Real-world DFMA — NCR POS terminal

NCR used DFMA to redesign a point-of-sale terminal, starting with assembly simplification (DFA) and then optimizing each remaining part for manufacturability. Manufacturability improvements at the part level—eliminating secondary operations, standardizing materials, simplifying tooling—compound on top of architecture-level wins.

Read the full NCR case study →

Manufacturability vs DFM vs DFMA

| Concept | What it is | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturability | A property of a design | How feasibly, consistently, and economically a part can be produced |

| DFM | A design practice | Improving manufacturability by adjusting geometry, specs, process, and material |

| DFMA® | An integrated methodology | Combining DFM (part cost) + DFA (assembly simplification) for total product cost |

You assess manufacturability to understand where the problems are. You apply DFM to fix them at the part level. You use DFMA to optimize total product cost by combining part-level and architecture-level improvements.

Frequently asked questions

What is manufacturability?

Manufacturability is the degree to which a part or product can be produced efficiently, consistently, and economically given a specific manufacturing process, material, and production volume. It's not binary—a part can be "makeable" but still fragile, slow, or expensive to produce.

What is the difference between manufacturability and design for manufacturability?

Manufacturability is the property of a design—how well it can be produced. Design for manufacturability (DFM) is the practice of improving that property by adjusting geometry, tolerances, materials, and process assumptions during design, when changes are cheapest.

How do you assess manufacturability?

Manufacturability is assessed by analyzing a design against the constraints and cost drivers of the intended manufacturing process. This includes evaluating geometry feasibility, tooling requirements, cycle time, setup complexity, tolerance achievability, and yield risk. Should-costing software like DFMA supports this by modeling process physics and quantifying the cost impact of each design decision, so teams can prioritize the changes with the greatest savings.

Why does manufacturability matter early in design?

Assessing manufacturability early—before tooling, supplier selection, or design freeze—means issues can be resolved with geometry or spec changes rather than expensive late-stage redesigns or production workarounds.

What are common manufacturability issues?

Common issues include tight tolerances that require slow machining or extra inspection, thin walls that cause warpage in molding, features that force secondary operations like EDM or hand finishing, geometries that require excessive setups, and specifications that limit supplier options or increase scrap rates.

Can software help assess manufacturability?

Yes. Should-costing software like DFMA models manufacturing processes from first principles—process physics, machine capability, material behavior, and tolerances—to build transparent cost estimates. By surfacing the biggest cost drivers and letting teams iterate on features and specs, it makes the cost consequences of manufacturability decisions visible and quantifiable.

See what's driving cost on your part

Bring a cost-critical part. We'll build a should-cost from process physics, show which features and specs are driving the number, and walk through the trade-offs—before your next design review or supplier conversation.