What is Design for Assembly?

Design for Assembly (DFA) is a methodology and set of tools used to analyze and reduce the assembly complexity of a product. It helps teams understand where time and cost accumulate during assembly—and where parts can be eliminated or combined without sacrificing required function.

DFA is most powerful when applied early: architectural choices lock in a large share of total cost long before a design reaches production.

- Fewer parts usually means lower labor, fewer defects, and simpler service.

- Minimum part criteria creates a repeatable decision test for consolidation.

- Quantify, then redesign. DFA compares iterations so teams converge faster.

On this page

Benefits: reduce total cost and improve reliability

DFA improves competitiveness by simplifying product structure so assembly becomes faster, more consistent, and less prone to errors. Unlike cost-reduction approaches that only target individual part prices, DFA targets total product cost by reducing: handling, fastening, alignment effort, inspection, and rework.

- Lower assembly labor content

- Reduced indirect/overhead load from fewer steps

- Fewer secondary operations and inspections

- Less rework and scrap from mistakes

- Fewer interfaces and failure points

- Reduced warranty/service complexity

- More consistent build outcomes

- Simpler training and work instructions

Why assembly labor matters

A common cost-reduction reflex is to make individual parts cheaper. That can help—but it can also backfire if it increases part count or adds difficult assembly operations (alignment, holding against forces, small fasteners, awkward access).

DFA makes these time sinks visible and measurable so redesign decisions focus on the few changes that move the needle most.

Core DFA principles

Use this checklist to spot high-impact simplification opportunities:

- Reduce part count by combining non-essential separate parts

- Eliminate fasteners where feasible (snap-fits, tabs, self-retaining features)

- Standardize components and reduce unique variants

- Minimize secondary operations and inspection steps

- Design parts for easy handling (avoid tiny, flexible, slippery items)

- Design for easy orientation (symmetry or clear asymmetry)

- Minimize re-orientation (reduce flips/rotations)

- Mistake-proof with poka-yoke features

Minimum part criteria: the method for "no part"

"Reduce part count" is easy to say and hard to do consistently. Minimum part criteria turns simplification into a repeatable decision test: does this part fundamentally need to be separate?

- Different material/process is required (insulation, wear, sealing, heat, conductivity, chemistry)

- Part must move relative to other parts to perform its function

- Must remain separate to enable assembly sequence, serviceability, or adjustment

If a part fails to justify itself on these fundamentals, it becomes a prime candidate to combine or eliminate—then you validate constraints and quantify impact.

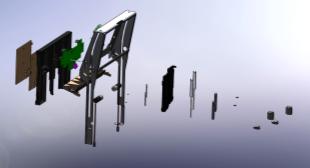

Quantified redesign example: IDEXX Catalyst Dx®

Medical device subassembly — 83% part reduction

At IDEXX Laboratories, R&D engineer Justin Griffin used DFMA software to redesign the Maintenance Access Door (MAD) subassembly on their Catalyst Dx® Chemistry Analyzer. The original design contained 183 parts and 63 torque-specified fasteners—each requiring a worker to tighten and mark it. By applying minimum part criteria, Griffin identified injection-molded plastics as the best substitute for sheet metal and fasteners, consolidating a 43-part main panel into a single molded piece with snap and slip fits.

183 → 31

63 → 0

45 → 11 min

5.8 → 3.5 lbs

| Metric | Original | DFMA Redesign | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of parts | 183 | 31 | 83% reduction |

| Fasteners | 63 | 0 | 100% eliminated |

| Assembly cost | $622 | $384 | 38% reduction |

| Assembly time | 45 min | 11 min | 75% reduction |

| Alignment time | 11 min | 3 min | 73% reduction |

| Weight | 5.8 lbs | 3.5 lbs | 40% reduction |

| DFA Index | 3.8 | 35.8 | 842% improvement |

| Out-of-box failures (loose hardware) | Possible | No hardware | Eliminated |

Real-world DFA results

Published DFMA case studies consistently show that systematic part-count reduction delivers large, measurable improvements. Here are documented results from named companies across industries:

- 55% part count reduction, 58% labor reduction

- 24% total product cost reduction

- Production throughput doubled

- 33% part count reduction

- 53% total cost reduction

- Enabled Southco to meet customer price target and improve profitability

- 27% part count reduction while adding features

- 50% decrease in build and test time

- Projected 50% warranty cost savings per unit

- 60% part count reduction on an example redesign

- Used Six Sigma to validate the statistical relationship between DFA metrics and factory outcomes

- 53% reduction in service call requirements

- Projected >$3M annual savings from a single machine redesign

- Avg. 35% part count reduction on new products

- Single 90-day session: 30% reduction (consumer electronics), 41% (TV), 57% (server)

Actual results vary by constraints, baseline design, and organizational readiness. DFA is most powerful when applied early and iterated with quantified comparisons. See all published case studies.

How to execute DFA: a practical workflow

- Baseline the current design (part count, assembly sequence, time drivers)

- Apply minimum part criteria to identify consolidation/elimination candidates

- Redesign the high-impact candidates first (fasteners, alignment-heavy ops, multi-piece housings)

- Compare iterations side-by-side; validate constraints (service, strength, tolerances, regulations)

To reduce total product cost (not just time), combine DFA with DFM should-cost analysis. Learn more about DFMA Product Simplification.

Implementing DFA in your organization

Teams get the best results when DFA becomes a standard review step—supported by training, a consistent method, and measured outcomes.

- Run DFA reviews early (concept + pre-design freeze)

- Make it cross-functional (design + manufacturing + assembly)

- Standardize outputs (baseline metrics + top redesign candidates)

- Track part count, assembly time, defects/rework, and service impacts

- Capture before/after comparisons to build internal credibility

- Use small wins to scale across programs

Frequently asked questions

What is Design for Assembly (DFA)?

DFA is a product development approach that simplifies product structure to reduce assembly effort—often by reducing part count, eliminating unnecessary fasteners, and improving handling and orientation during assembly.

How is DFA different from DFM and DFMA?

DFA focuses on reducing assembly time and complexity. DFM focuses on designing parts that are easy and economical to manufacture. DFMA combines both perspectives to optimize total product cost and producibility.

What is minimum part criteria?

It's a structured test that challenges whether a part must be separate for fundamental reasons: different material/process, required relative motion, or necessary separation for assembly/service/adjustment.

When should we apply DFA?

As early as possible—during concept and early CAD iterations—before the design is locked and tooling or supplier commitments are made.

How does DFA software help?

DFA software quantifies assembly effort, highlights high-impact simplification opportunities, and supports side-by-side comparison of redesign iterations so teams can converge faster and standardize results.

Does DFA always reduce cost by 50%?

Results vary by product, baseline complexity, and constraints. Many organizations achieve meaningful reductions in part count and assembly time when simplification opportunities exist, but the exact savings depend on the starting design and manufacturing context.

Want to see DFA applied to your product?

Bring a "painful" subassembly (fasteners, alignment, rework). We'll show how minimum part criteria identifies consolidation candidates and quantifies the impact.